Kung fu movies are amongst the most successful cultural exports from Greater China, and especially Hong Kong.

Many people know how the films produced in Hong Kong from the 1960s on built on the tradition of Cantonese opera, with its slapstick and acrobatics.

However, fewer people in the west appreciate that Chinese literature also boasts a longstanding martial arts (武侠 – literally martial heroes) tradition.

The Water Margin

Perhaps the most famous Chinese wuxia novel is The Water Margin (水滸傳), which tells the tale of a band of outlaws and misfits, who boast martial prowess, but live on the fringes of society at the tail end of the northern Song period, in the 1120s.

The book was written by Shi Naian (施耐庵), who lived from about 1296 to 1372. Little is known of Shi, though, barring that he lived at another time of turmoil at the end of the Yuan dynasty; civil wars, famine and rebellion eventually brought the brutal Zhu Yuanzhang (朱元璋) to power as the first Ming emperor (明太祖) in the 1380s.

The book is itself set in an earlier era of instability (much like that of Shi Naian’s own time), with the bandits acting as folk heroes (or anti-heroes), akin to Robin Hood and his Merry Men in British tradition. The heroes engage in sometimes hard-to-justify fights and feuds, and generally act in a likeable, if somewhat chaotic, fashion.

The Water Margin has enjoyed huge prominence in China over the centuries. It was a favorite of Mao Zedong, for instance, perhaps because he recognized something of the experience of the characters in The Water Margin in his time as a Communist “bandit” leader in the Jiangxi Soviet in Jingganshan from 1931.

Military parade in Jiangxi Soviet

In a sad twist, Mao actually later made use of the book towards the end of the Cultural Revolution, launching in 1975 a campaign based on the character Song Jiang’s acceptance of an amnesty from the emperor – which Mao saw as “capitulationism”, and a repudiation of the Cultural Revolution itself. Mao enjoyed abstruse literary references.

Wu Song and the tiger

The Water Margin was first translated into English by the American writer Pearl S Buck, as All Men Are Brothers in 1933. She famously also wrote The Good Earth.

One of the most famous of the stories in The Water Margin is about Wu Song (武松), also known as Pilgrim Wu.

In essence, Wu Song, who fights with a staff (棒) and two swords in the book, is travelling on a road into the mountains, towards the Jingyang Ridge (景陽岗) when he comes across an inn.

On the wall of the inn is a sign saying: “After three bowls [of wine], do not cross the ridge” (三碗不過崗). The innkeeper then explains that the reason for the sign is that his wine is strong.

Wu Song is a bit of a braggart, though, and gulps down three bowls, and then demands more, not feeling tipsy at all. He greedily consumes a good meal with 18 bowls of the wine, and stands to leave.

The innkeeper begs him to stay, though, explaining that the sign is on the wall because a ferocious tiger lurks on the ridge, and that those travellers who are too drunk fall prey to the hungry beast.

Wu Song thinks the innkeeper wants to gull him into staying the night, however, and so ignores the warning, barges through the door, and stumbles onto the road.

On reaching the ridge, however, he sees an official sign warning about the tiger, confirming the innkeeper’s warning. Wu Song is scared, but does not want to lose face, and so stumbles on.

Before long, the wine takes its toll, and Wu Song sits down and falls into slumber. The tiger then leaps out of the woods, attacking Wu Song.

The startled warrior jumps up and fights back, but does not have his swords, and breaks his staff on a tree.

Somehow, though, he manages to climb onto the tiger’s back, and to pin down the beast, before battering it to death with his bare hands.

Wu Song quickly flees the spot, chastened and fearful that another tiger will emerge from the undergrowth.

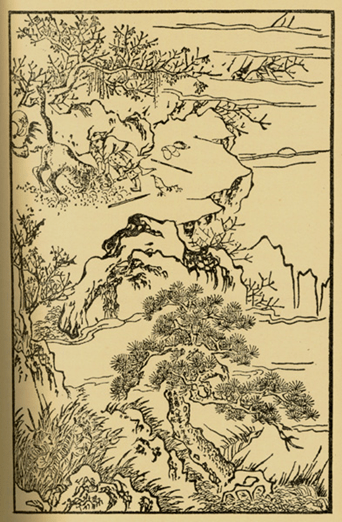

Wu Song kills the tiger

The story is one of the most beloved in Chinese literature, and also a favourite for Chinese television serials, made over and again across the Chinese-speaking world.

The book is well worth a read.

Leave a reply to Paul Lillie Cancel reply