The imposition of tariffs on Chinese goods by US President Trump threatens not only wrenching changes to the largest bilateral trading relationship in the world, but also undermines efforts to deter China from action against Taiwan. As such, the tariffs make the world a much more dangerous place.

The trade war

Discussion of the tariffs has focused on rises in prices in the US, the loss of market access for Chinese producers, and the prospect that cheap Chinese goods will flood into other markets. These issues certainly bear consideration, although the complexity of international trade makes calculating what will happen hard, if not unknowable.

What does seem likely, though, is that the tariffs will have a major strategic impact – just as the Smoot-Hawley tariffs of 1930 impelled self-perceived “have not” states, such as Germany, Italy and Japan, to invade weaker parties, so as to secure access to markets and resources.

Smoot and Hawley

The strategic implications

Japan’s dealings with the US prior to the outbreak of the Pacific War on 7 December 1941 are worth running over in this context.

Japan’s biggest export to the US prior to the depression was silk, but Tokyo was acutely reliant on the US and western European empires for key inputs, such iron and steel, aluminum, and, most importantly, oil.

Japan’s strategists were aware of this vulnerability, and some groups sought to overcome the shortfall by expanding into Manchuria in 1931, and then into northern China.

Eventually, Japanese expansionism, driven forward by its wildly insubordinate military, resulted in overt conflict with China breaking out in June 1937.

US export controls

Tokyo’s stance towards China conflicted with Washington’s longstanding Open Door policy, and so, throughout this period, the US opposed Japanese actions in China.

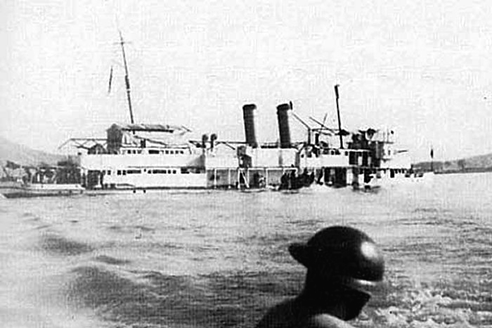

Even so, it was only after the conflict in China broke out in 1937 that the US imposed major trade restrictions on Japan. A key moment here was the bombing of the USS Panay on 12 December 1937 by Japanese planes, which enraged American public opinion.

The USS Panay sinking after a Japanese bombing run

As the Sino-Japanese war intensified, the US expanded restrictions, starting with a “moral embargo” on aircraft exports, moving to restrictions on high-octane aviation fuel, and later including scrap metal. US policymakers effectively sought to deter Japan from further military action by threatening the strangulation of its economy.

A crisis point came after the German invasion of Russia in May 1941, which prompted Tokyo to order forces into the southern portion of Vichy France-controlled Indochina. Washington responded by restricting all oil exports to Japan and by freezing financial assets.

The impact was immense. The Imperial Japanese Navy was especially concerned, fearing the suspension of operations within six months for lack of oil; Japan was a “fish in a draining pond”.

Japan’s leaders concluded that the only reasonable response was to seize oil fields in the Netherlands Indies – and that to do that safely, Japan would need to strike at the British in Singapore, and at US forces in Hawaii.

A good book on this dilemma is Bankrupting The Enemy: The US Financial Siege of Japan Before Pearl Harbour by Edward S Miller.

A failure of deterrence

Of course, China today, a continental, manufacturing behemoth, differs hugely from Japan, then a maritime empire juggling resource shortages, and with an army running amok across northern Asia. China is obviously much less vulnerable to blockade than is Japan.

Even so, in one key respect, a comparison is worth making. What is notable in the Japan case was that the US policy of deterrence based on economic coercion failed utterly.

In effect, US actions removed cause for constraint on Japan’s part, by cutting off trade in oil and freezing assets, so forcing Tokyo’s decision makers into a choice between a gamble on a surprise attack on Pearl Harbour, or acceptance of defeat.

US decisions may have been justified, but they failed to deter Japan.

Lessons for Taiwan

That failure of deterrence is worth bearing in mind in relation to any prospective action by Beijing against Taiwan.

After all, a threat of serious damage to the immense Sino-American trading relationship had (presumably) hitherto forced China to think hard before military action.

Now, President Trump’s actions have done away with that constraint (short of a resolution to the trade dispute). The trade war could well raise the risk of war in the Taiwan Strait.

Leave a comment