A series of recent reports have raised the prospect of major technology companies, and other businesses, moving production out of China.

However, these reports often understate the challenges involved in any such restructuring, and the timeframe within which it can take place – as the case of Vietnam makes clear.

De-risking is certainly happening, but is perhaps easier said than done.

Demand for de-risking

Much mainstream media reporting has drawn attention to foreign investors’ shifting away from China in recent years, so “decoupling” or “de-risking”.

The most obvious shift has been in terms of portfolio capital, with many US funds directing money elsewhere, in response to weakening economic fundamentals, and regulatory pressures in the US or elsewhere. A brief uptick of flows into stocks earlier in 2024, in response to the cheapness of Chinese shares, has not reversed this trend.

Industry is also said to be de-risking. Manufacturing companies most frequently mentioned as liable to move have included semi-conductor and high-technology manufacturers, many of which have had to scale back aspirations in the face of US restrictions.

Indeed, ASML, the Dutch manufacturer of machine tools for the making of semi-conductors, may soon cease maintenance work on machines in China, because the Netherlands’ authorities are likely to refuse to renew relevant licences.

A report issued in September 2024 by Standard & Poors also made clear that many US and other businesses in the electronics sector are seeking to invest in production facilities outside China, in states such as Vietnam or India.

In doing so, such firms are reportedly building on what has become known as a “China Plus One” strategy – a hedging strategy of sorts.

The reality

Reports of this restructuring receive much media attention, and are certainly under way, but these reports do not tell the whole story. After all, other businesses show little to no sign of de-risking or decoupling.

Germany’s vast car industry is one example. Notwithstanding the competitive threat posed by Chinese electric vehicle manufacturers, firms such as Volkswagen continue to invest heavily in the People’s Republic of China (“PRC”).

Mercedes dealership in Zhengzhou

Germany’s Bundesbank published data in August 2024 suggesting that German investment into China could double in 2024; USD7.3 billion has already been invested in the first half of 2024, up from USD6.5 billion in all of 2023. The German car firms may be seeking access to pioneering battery technology from Chinese firms, in a reversal of recent industrial history.

Away from the commanding heights of the economy, other manufacturers in uncontroversial sectors are themselves loath to abandon profitable, smoothly running, and long-established facilities, built through sweat and treasure. These non-political businesses simply hope to keep their heads below the parapet, and to continue to trade.

The upshot is that China’s already huge role in global trade continues to grow, notwithstanding talk of decoupling; and this expansion is that much more remarkable for coming in the face of geopolitical tensions, demographic weakness, and the property and debt malaise.

The alternatives

A separate, if less-discussed, problem for investors is that the alternatives are not really that attractive.

Take Vietnam. That country has grown rapidly in the last two decades, expanding infrastructure and becoming a major economic “tiger” in its own right. Its successes are clear, and much trumpeted.

Even so, Vietnam still lags China by years, if not decades. Its infrastructure is frailer, as electricity outages in 2023 made clear, its rule of law is less predictable, as borne out by a recent corruption case in the financial sector, and the capacity of Vietnamese workers, while rising, is still well below that of China.

Vietnam’s labour costs are lower, of course, but China’s progress in terms of automation of plants may soon compensate for that weakness.

Still exposed?

A separate issue is that a move may not even protect a company.

Many Chinese companies have invested in Vietnam in recent years, so as to circumvent US restrictions. Vietnam’s Ministry of Planning and Investment noted that as of June 2024, Chinese investors accounted for 29% of new ventures in Vietnam in the last year, the highest number from any state.

A shift to Vietnam may leave firms exposed to Chinese providers, then, not least as policing sub-tier suppliers is hard enough in China, but harder still in Vietnam, given levels of corruption and the less structured commercial environment.

Appraising this situation, companies may simply decide that de-risking not only makes no commercial sense, but scarcely reduces risks.

Vietnamese hedging

A final point is that Vietnam’s relations with China are not straightforward, either. The western media tends to depict China as an ancestral enemy of Vietnam – and there is something in that.

Hanoi has certainly looked warily to its north since independence from China in the tenth century, all the way until the 1979 border war. The Chinese have invaded time and again, and the two states still dispute the South China Sea.

Qing soldiers invading Vietnam in 1788 to 1789

Equally, though, cultural affinities and a shared Communist history are just as important.

Vietnam’s “founding father” Ho Chi Minh spoke Chinese (both Cantonese and Mandarin) fluently, and spent much time in China in the 1920s and 1930s. Beijing also backed Vietnam during its war with the US; many thousands of Chinese troops manned anti-aircraft weapons.

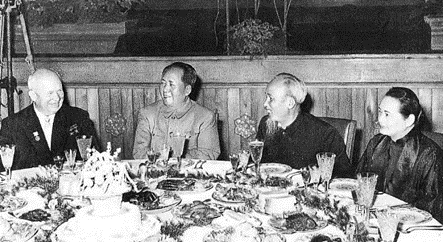

Khrushev, Mao, Ho Chi Ming and Soong Qing Ling eating dinner in 1959

Reflecting this complex relationship, Vietnam’s new President To Lam first visit was to Beijing, shortly after taking office in late August 2024. That he travelled there ahead of Washington hinted at Hanoi’s own hedging strategy. After all, the US has not granted Vietnam market-economy status, yet, which would have allow for more advantageous trading terms.

The perils of decoupling

All told, then, reports of manufacturing shifts away from China in the media are accurate, but still disguise a great deal of nuance and complexity. “De-risking” is under way, but is patchy, and perhaps easier said than done.

Leave a comment