The victory of Prabowo Subianto in the Indonesian presidential elections has drawn attention to the former special forces general’s links to Suharto’s New Order (Orde Baru) – and is thus a reminder of the prominence and plight of the Chinese business community in Indonesia at that time.

The elections

Prabowo won the polls convincingly, although the formal count is not yet complete, and he will not take office until October 2024. His victory owed much to the support of the popular current President Joko Widodo.

However, Prabowo’s victory also drew attention to his ties by marriage to (and divorce from) Titiek Suharto, the second daughter of the former dictator.

Of further note were his links to human rights abuses in East Timor, and alleged involvement in the disappearance (and presumed murder) of perhaps 22 student activists in 1998.

Prabowo reviewing troops in 1998

The 1998 protests

The media focus on Prabowo’s alleged involvement in the disappearance of the students has also recalled how, during Suharto’s fall from power in May 1998, protesters carried out racist attacks on the Chinese minority.

Rioting in May 1998

Those attacks came about in part thanks to envy at the commercial success of the Chinese minority, and resentment deriving from their perceived corruption.

After all, Suharto did rely on a coterie of immensely successful Chinese business cronies, who became the commercial face of his regime, even if most of the victims of 1998 were ordinary people.

The old guard

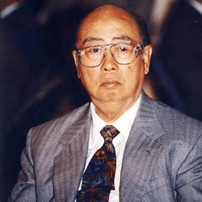

Perhaps the best known of the tycoons was Lim Sioe Liong (林紹良), also known as Sudono Salim. He was born in Fuqing (福清市) in China’s Fujian province in 1916.

Lim Sioe Liong

After Suharto took power in 1965, his Salim Group grew to control interests as varied as radio and television, mobile telephony, instant noodles, convenience stores, and car sales, thanks to Suharto’s patronage.

The family’s prosperity and prominence, though, resulted in targeting when the 1998 financial crisis hit. The Salim home was burnt to the ground, Sudono Salim and his family fled to Singapore, and subsequent investigations highlighted his role in managing the financial interests of Suharto’s relatives (known as the Cendana family).

Another prominent Chinese-Indonesian tycoon from this era was The Kiang Seng or Mohamad “Bob” Hasan. He was known as the “plywood king” owing to his control of the timber industry through Kalimanis Group. Bob Hasan briefly held the post of trade minister in 1998, but was imprisoned from 2001 to 2004 for corruption; people remembered his dealings with Suharto.

These conglomerates lost sway after the fall of Suharto, but remain prominent, nonetheless. The Salim Group is still amongst the biggest in Indonesia, for instance, now under the control now of Sudano Salim’s son Liem Hong Sien (林逢生), or Anthoni Salim.

Fujianese links

One interesting feature common of many of the tycoons in Indonesia was a link to Fujian province – and more precisely to the district around Fuqing city. There, they speak a separate dialect (福清话 – pronounced Hokchia locally), which is distinct from Fujianese, if mutually comprehensible.

For instance, Sudono Salim, and his partner Sutanto Djuhar or Liem Oen Kian ( 林文镜), both came from Fuqing, while the parents of Mochtar Riady or Lie Mo Tie (李文正), the founder of Lippo Group, hailed from Putien (莆田), also close to Fuqing.

The Sampoerna family, which dominated the production of kretek or clove cigarettes for many years, came from Anxi (安溪) county in Fujian.

This Fujianese role in Indonesian business came about in part owing to the poverty in that province, with its geography of overpopulated, narrow valleys running to the sea; there was scant land for farming.

People had little choice but to turn to the sea, trading, fishing or engaging in piracy to make ends meet – which resulted in their becoming amongst the most outward-looking and enterprising people in China.

Those who emigrated also benefitted from links to regional networks that communicated in Chinese (seemingly impenetrable to many outsiders), and shared information through newsletters and native place associations.

That transnational perspective afforded the Chinese advantages in identifying and responding to commercial opportunities, which were generally not available to the local populace.

Of course, traditional Chinese values of hard work and frugality also assisted in winning success – but money lending and tough deal making also engendered resentment.

What next?

How Prabowo will handle this delicate legacy is not yet clear.

The incoming president benefitted from ties to the tycoons, but he is also an Indonesian nationalist. It is thus possible that he could revert to nativism, particularly if tensions rise over Beijing’s claims to waters near the Natuna islands in the South China Sea.

Should he do so, there is much resentment to draw on, as made clear by the downfall of Basuki Tjahaja Purnama or Ahok (阿學), a Chinese politician who became governor of Jakarta in 2014.

Ahok was ousted in an electoral campaign built on anti-Chinese feeling in 2017, and, to add insult to injury, imprisoned for two years for blasphemy (he is a Christian).

For now, Prabowo shows few signs of stoking nativism – but that could change. Either way, his election is a reminder of the Suharto era, and all of its complexities for the Chinese community.

Leave a comment