An exhibition at Singapore’s Asian Civilisations Museum, Manila Galleon, provides some insights into trans-Pacific trade in the sixteenth, seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.

In particular, the exhibition provides a viewpoint into how Spanish galleons plied across the Pacific and so tied Europe, Mexico, the Philippines, and China together in a web of commerce for several hundred years.

Trans-Pacific ties

The exhibition offers up some artistic wonders, including silver caskets for holding the eucharist, and chocolate or coffee pots made from Chinese ceramics, which sat on Mexican tables.

A picture of a galleon from 1590

Some examples are truly striking, such as dresses woven in the Philippines from pineapple fibres, known as piñas. These textiles became hugely popular at the Spanish Bourbon royal courts in the eighteenth century.

18th Century piña textiles

The hunt for silver

What the exhibition makes clear, too, though, is that underpinning the trade was silver. After all, the Spanish conquered the New World in pursuit of treasure, and the Potosi silver mines (now in Bolivia) provided an enormous influx of coin into Europe and Asia.

A “great inflation” took place in Europe, from the late fifteenth century into the seventeenth century, which some claim provoked a commercial revolution across the continent. Much of this silver (perhaps 30% or more), though, eventually found its way to China, in part owing to a higher price for the metal there than in Europe.

After all, demand for silver was especially strong in China after 1540, when the Ming dynasty moved away from the copper and paper-based currency system imposed by the founding Ming Hongwu (洪武帝) emperor, Zhu Yuanzhang. China had few sources of silver, though, and so people sought the metal from trade.

A growing trade

Initially, the Portuguese acted as the middlemen for the provision of silver to Ming China.

This trade went in large part through Macau, which was founded as a trading post in 1557, with silver coming from Mexico to Portuguese ports (then under the control of King Philip II of Spain), and in time being exchanged in Asia for Chinese goods such as silks and ceramics.

However, the direct galleon trade from Mexico to the Philippines, emerging after the Spanish takeover of Manila in 1571, provided an alternative route for silver exports across the Pacific, so integrating the Americas directly into this trade. The first cargo of Chinese goods sailed from Manila to Acapulco in Mexico in 1573.

Pirates, as ever, scented opportunity quickly. The Chinese (Teochew) pirate Lin Feng (林鳳) or Limahong, attacked Manila and invaded the northern Philippines in 1574, for instance, and Sir Francis Drake, the English privateer, hunted for Spanish treasure ships going to Manila off the California coast in 1579.

Tensions in Manila

The Chinese quickly came to dominate the Manila trade, at least in the Philippines, as traders from Fujian built on their knowledge of the regional sea routes, and leapt on the commercial opportunities. Chinese numbers in Manila grew rapidly, far outnumbering the Spanish, by 10,000 to 2,000, by 1586.

Tensions rose in response, though, exemplified in nasty incidents, such as in 1593, when Chinese rowers for Governor Gomez Perez Dasmarinas rose in mutiny, and murdered the grandee. Those rowers fled to Vietnam, although a few were later captured in Portuguese Malacca, and were brought back to the Philippines for execution.

Rumours of gold deposits, and frictions over Ming officials’ efforts to impose justice on Chinese residents of Manila, led later to a larger-scale uprising in 1603 by the Chinese population, called the Sangley Rebellion.

The Spanish put that uprising down, with help from Japanese samurai mercenaries, but with a massacre of perhaps 20,000 people. Even so, the Chinese quickly returned, as the Spanish recognized that their industry and trading formed the basis of Manila’s prosperity.

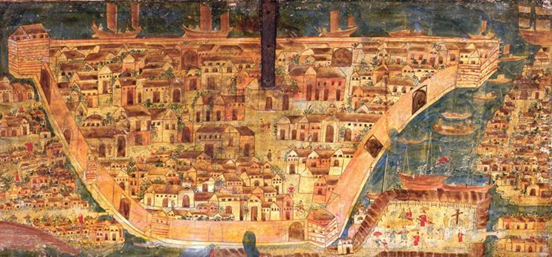

As it happens, one of the items in the exhibition in Singapore is of a wooden chest, borrowed from the Museo de Arte Jose Luis Bello in Puebla, Mexico.

The inside of that chest, dating from the 1640s, has painted on it a map that may be of Manila from before the destruction of the Chinese town, giving a sense of how prosperous it must have been.

The map of Manila inside the chest

The end of the trade

The exhibition in Singapore is fascinating, then, as a reminder of how rich but conflicted the regional commercial legacy can be.

Leave a comment