Slides in the Chinese stock market may mark the last gasp of the policy settlement that emerged in China in the 1980s – a mix that underpinned one of the most extensive periods of growth in economic history.

The fall

Key share benchmarks in China have tumbled in recent weeks, with the Hang Seng Index in Hong Kong sliding to 14,961 on 22 January 2024, down from over 20,000 in August 2023.

The declines came about in part owing to the flight of foreign capital from the market, and in part owing to a broadening sense that the economic outlook in mainland China shows few signs of improvement.

In response, the Beijing government has taken some steps aimed at shoring up the situation.

Of note, certain brokers have responded to requests to retain holdings in mainland markets, and Central Huijin (中央汇金), a state-controlled sovereign wealth fund, has bought exchange traded funds. More such actions may follow.

These measures partly recall the involvement of the “national team” (国家队) in the stock markets after the collapse of mid-2015, when the government made clear to traders that selling was “unpatriotic” – although no corrective measures have yet gone as far as then.

Looking forward, many commentators are focusing on whether, or when, the central government will intervene – either with administrative steps limiting sales, or with wider efforts to reignite economic growth.

Regardless of what happens next, though, the truth is that the market declines make clear just how far China has shifted away from the policy mix drawn up in the 1980s – and back towards statism.

To get rich is glorious

That policy mix emerged from a debate in economic statecraft in the 1980s, which took place under the aegis of Chinese Communist Party (“CCP”) General Secretary Hu Yaobang (胡耀邦) (in post until 1986), and his successor, Zhao Ziyang (赵紫阳).

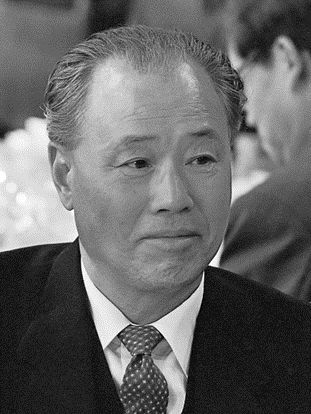

Zhao Ziyang

These two leaders advanced Deng Xiaoping’s Reform and Opening Up process (改革开放) – Zhao even reportedly favoured a degree of political liberalization.

At first, growth moved forward at a rapid pace, but inflation rose in the later 1980s, as limited capacity and the impartial nature of price reforms impinged on activity. Similarly, protests precipitated by the sudden death of Hu Yaobang led to the Tiananmen Square massacre in the summer of 1989, and a round of political repression.

In response to the chaos, Deng Xiaoping removed Zhao from office, and a shift away from liberal reform followed, with the temporary return to influence of key conservatives, such as then Premier Li Peng (李鹏) and Chen Yun (陈云).

However, Deng Xiaoping’s Southern Tour in 1992 (九二南巡) led, again, to a reversion towards a more capitalist approach – albeit with political reforms entirely off the agenda, and with policymaking containing a never-renounced streak of statism.

An excellent book on the debates at this time is Never Turn Back by Julian Gewirtz.

Statue commemorating the 1992 Southern Tour

That policy mix continued for the subsequent generation, with both CCP General Secretaries Jiang Zemin (江泽民) and Hu Jintao (胡锦涛) leaving in place measures that led to widespread economic growth, albeit without relaxing CCP control.

That era had its flaws, such as environmental harm and corruption, but also resulted in China’s integration into the world economy, and prosperity for many. A strong demographic structure aided expansion, of course.

The pendulum swings back

Sadly, that era appears to be over.

In particular, since 2012, the Chinese government has moved back to a more state-centric approach to economic policymaking, even as the demographic structure has deteriorated, and as external tensions have grown.

This shift has taken time, but has become exemplified in measures such as:

- steps to rein in overmighty conglomerates, such as Tomorrow Group, Anbang Insurance, and HNA Group;

- actions against technology businesses, such as Alibaba;

- continuing anti-corruption initiatives;

- restrictions on local government raising of debt;

- the creation of a “traffic light” system to channel capital towards chosen industries; and

- industrial planning aimed at building up sectors such as electric vehicles, semi-conductors, and other high-technology industries.

The result is a much more constrained market environment, and a shift away from the trend towards economic liberalization.

The fall in the stock market, then, is not just a capitulation in the face of weak economic data, but rather marks the last gasp of the 1980s settlement in China – and of a flawed, if free-wheeling, period in Chinese history.

Its passing will probably be regretted.

Leave a comment