A recent exhibition at the Hong Kong Palace Museum about the Sanxingdui (三星堆) bronzes highlights how little is really known about the earliest periods of Chinese history. Indeed, the bronzes speak to a vision of the world at huge variance with other ancient cultures not only in China, but also around the world.

An archaeological mystery

The exhibition shows off a series of bronzes found at a place called Sanxingdui in Sichuan province in 1986, which were seemingly demonstrative of the ancient culture of Shu (蜀). The items discovered included ancient carved jades, weapons, and scorched bones and tusks, which appear to have been deliberately destroyed and buried in pits.

The bronzes date from about 1200 to 1100 BC, and are significant because they demonstrate that a culture emerged in Shu independently of the civilisations in the Yellow River basin – notably the Shang dynasty, which is most closely associated with the origins of Chinese culture. The distance between the two areas is perhaps 750 km, separated by mountains, suggesting that links were probably limited.

This Shu culture appeared to thrive for something over 300 years, from perhaps 1600 BC to 1100 BC, but disappeared with little trace. A comparable culture sprang up later at Jinsha, about 30km from Sanxingdui, which most archaeologists accept is descended from that at Sanxingdui. However, the cause for the move is not clear; some archaeologists blame earthquakes and flooding.

Sadly, virtually nothing is known from written sources about Sanxingdui, with most writings relating to a much later period – as much as a 1,000 years later, when Shu’s absorption into the state of Qin provided the basis for Qin’s later establishment of the first empire.

The bronzes

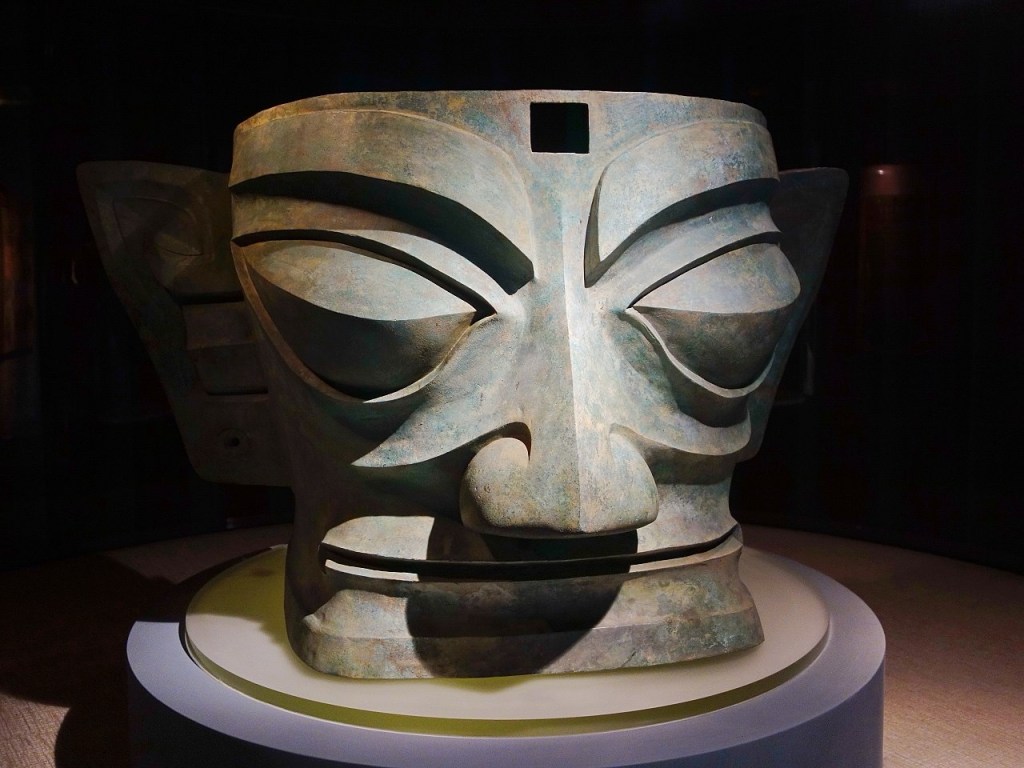

The bronzes are so striking not only because of the seemingly sophisticated casting techniques needed to make them, nor because of the traces of paint or gold leaf on the bronzes – although these features are certainly noteworthy.

Rather, it is their otherworldly nature that is most impressive, and their sheer difference from the Shang artistic tradition.

A bronze mask with gold leaf

A quick glance is perhaps enough to highlight the differences. The main features of the Sanxingdui bronzes are their huge faces, with exaggerated but simple features. By contrast, Shang artefacts show intricate carving with a different feel.

A Shang box

A Shang dynasty bronze

The eyes have it

One feature is an emphasis in some Sanxingdui masks on eyes, which some have said relates to the founding King of Shu, Cancong (蠶叢), who reportedly had bulging eyes and wore colourful silk clothes. Equally possible is a religious interpretation, with eyes having some symbolism now lost to us.

A bronze mask with bulging eyes

With regard to religion, another statue of note is of what may be a sacred tree, standing 3.95 m tall from a circular base, with branches radiating out, each adorned with leaves and ending with a single piece of fruit.

A sacred tree from Sanxindui, from the 12th or 11th century BC

The restoration of the tree was a feat in-and-of itself. Archaeologists painstakingly reassembled it over eight years, but still do not know what its purpose may have been.

Some people contend that the presence of the fruit pointing upwards with birds perched on top was part of the Ancient Shu people’s worship of the 10 suns. In that myth, the birds were said to carry the suns on their back.

Other statues

For me, though, the most striking a statue is of what seems to be a religious or civil official, with a narrow waist, who was originally holding a spear or staff.

The statue must have loomed high, demanding respect of worshippers or subjects.

A varied story

The Sanxingdui bronzes, then, invite us to ask deep questions about assumptions made for so long about the emergence of Chinese civilization – and highlight, as ever, how sprawling and varied is the story of China.

Leave a comment