The approval of a Resolve Tibet Act by the US House of Representatives Foreign Affairs Committee on 29 November 2023 has underlined how the Tibet issue will play into Sino-American relations in the coming months. The act also draws attention to the complexity of the question of Tibet in the context of Chinese Buddhism.

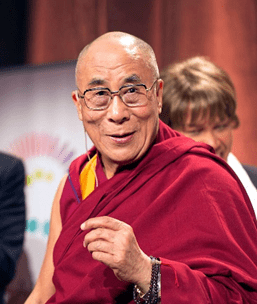

A frail Dalai Lama

The Promoting a Resolution to the Tibet-China Dispute Act (its full name) sets out provisions that would reject China’s claims to Tibet, and calls on China to resume negotiations with the Dalai. The act would also require the US government to counteract Chinese assertions about Tibet, with a public diplomacy campaign.

The US Congress has yet to pass the law, but such provisions would certainly enrage Beijing. Moreover, the law is timely; this issue will become much more contested in the months to come, given the Dalai Lama’s age, and rumors of his ill-health.

The Dalai Lama

In particular, after the Dalai Lama dies, the Chinese Communist Party (“CCP”) seems likely to seek to identify his reincarnation, and take that person under control – as it did with the Panchen Lama, Gedhun Choekyi Nyima, in 1995.

Such actions, though, will have major implications not only in Tibet, but more widely amongst Buddhists in India and elsewhere. Indeed, the Cold War context of relations means that this issue will surely add to Sino-American tensions.

Cultural cross over

Putting these political issues aside, though, the selection of a new Dalai Lama will also have complex cultural repercussions across the Chinese-speaking world.

After all, just as the Panchen Lama is considered to be the reincarnation of Amithaba, the Buddha of the Western Pure Land, so is the Dalai Lama the reincarnation of the Boddhisatva of Compassion, Avalokitesvara.

Across the Chinese world, however, people worship an altogether different manifestation of Avalokitesvara, the goddess Guan Yin (觀音). These conflicting visions of the same deity will thus play into the broader debate about Tibet, and perceptions of how to handle this issue.

Buddhism in China

Avalokitesvara, generally known in China as Guan Shi Yin (觀世音), or The One Who Perceives the Sounds of the World, arrived along with Buddhism towards the end of the Han Dynasty in the second century AD. Buddhism came with travellers on the Silk Road, its sutras tucked away in saddlebags on camels and horses.

Initial representations of Avalokitesvara were male, as in India at that time. However, people often turned to the Boddhisatva for solace, and to ask for children, and by the start of the Song Dynasty in 960, Avalokitsevara had become Guan Yin, the graceful female whose statues now stand in so many Chinese temples.

A Ming Dynasty statue of Guan Yin

Adoption by myth

Stories about Guan Yin’s origins also grew up across China, hinting at how ordinary people integrated Avalokitesvara into their lives.

These myths vary, but a rough version was that Guan Yin was Miao Shan (妙善), a princess and the daughter of a cruel king, called Miaozhuang Wang (妙庄王), who ruled in the sixth century BC.

Miao Shan was beautiful, kind and devout, and given to caring for others. She wished to become a Buddhist nun, rather than marry, as her father demanded. Miaozhuang Wang thought that a nunnery was no place for a princess, though, and tried hard to change her mind.

Miao Shan was resolute, however, and her father became so enraged by her unwillingness to comply that he ordered her execution. Versions here vary, but either after her execution, or in order to save her, a magical tiger appeared, and carried Miao Shan away on its back.

The tiger then brought her to one of the halls of hell. In the underworld, though, Miao Shan played music, and flowers blossomed around her, upsetting Yama (閻王 – Yan Wang), the fierce King of the Underworld. Yama saw his place of punishment turned into a unfitting paradise, and so decided to allow Guan Yin to return to life, so as to dedicate herself to Buddhist devotions and good works.

In the interim, her father, Miaozhuang Wang had fallen ill, and demanded of his quailing doctors a cure. They had no means of helping, but a monk suddenly appeared, and told the king that making a medicine from the eye and arm of a person without anger would heal the illness. The monk knew of a nun who fitted this description, who was Miao Shan.

Envoys from the king then visited Miao Shan, and asked for her help. She immediately gouged out her eye and cut off her arm, so that the doctors could make the medicine. Her father was then healed, but was later aghast to learn that his own daughter had given her eye and arm to heal him. Miao Shan subsequently transformed into the Boddhisatva of Compassion, Guan Yin.

A much-loved, but complex heritage

Shrines to Guan Yin are now found throughout the Chinese-speaking world, drawing in all those seeking support in difficult times. Guan Yin is much-loved, as a kind and graceful figure. She appears in many guises, not least in support of Sun Wukong (孙悟空), the Monkey King, on his quest in Journey to the West (西遊記).

The Tsz Shan Monastery in Hong Kong

However, her myth is also much debated, for one thing in the contest of the complex history of women’s standing in China; her story is one of sacrifice, but also of rebellion. The notion of giving over her flesh to heal her father is also a fine exemplar of the Confucian virtue filial piety (孝), linking her to Confucian tradition. Similarly, Christian missionaries later sought to draw (perhaps overstated) parallels between Guan Yin and the Virgin Mary.

Back to Tibet

In the context of contested control of Tibet, though, perhaps the true marvel is that Guan Yin and the Dalai Lama are manifestations of the same Boddhisatva; and that both proffer the same kindness, love, and compassion.

Importantly, too, these differing cultural perceptions of a key figure in Buddhism overlay (and perhaps complicate) the debate about how to respond to the Chinese Communist Party’s control of Tibet.

Leave a comment