The return of two pandas on 8 November 2023 from the US to China suggests that structural differences in Sino-American ties will prove hard to surmount, notwithstanding a promised meeting between US President Joe Biden and Chinese Communist Party (“CCP”) General Secretary Xi Jinping.

Proxy diplomacy

The pandas’ departure is important, because the bears have long been a symbol of Chinese diplomacy – and hence a proxy for ties with China.

The bears’ role in diplomacy role is old. Indeed, some reports suggest that Wu Zetian, the only female emperor of China, sent pandas to Japan in the 7th or 8th centuries.

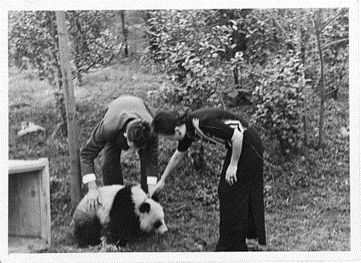

More recently, Soong Meiling, the glamorous wife of Kuomintang leader Chiang Kai-shek, and the embodiment of wartime China’s close alliance with the United States, delivered two pandas to the Bronx Zoo in 1941, called Pan-Dee and Pan-Dah. Their delivery coincided with the Pearl Harbour attacks, though, and so received little media attention.

Soong Meiling and a panda

Post-liberation panda diplomacy

After liberation in 1949, “red” China refused to share pandas with the US; Cold War allies such as the Soviet Union and North Korea instead received pandas instead (a number of those in North Korea died early).

The Nixon visit to China in 1972 eased the way for better relations, though, and new Chinese pandas came to American US zoos; Ling-Ling and Hsing-Hsing arrived months after Nixon returned to the US, causing “panda-monium” amongst the public.

In return, Richard Nixon gave China two musk oxen in February 1972, Milton and Mathilda, prompting a generation of jokes about who got the better of that trade. The pandas lived for years, but Milton died of eating a sharp object in 1975, and Mathilda of undisclosed causes in 1980.

A musk ox: not as pretty as a panda.

Edward Heath, the UK’s Prime Minister, brokered a similar deal in 1974, bringing Chia Chia and Ching Ching back to the UK.

A cannier approach

The panda trade shifted under the canny Deng Xiaoping. Deng halted the gifting of pandas as a purely diplomatic tool, and established instead a leasing system. In doing so, he combined diplomatic bonhomie with sharp business practice.

The leases have since become the mainstay of the panda trade, although some zoos have grumbled that the pandas have become a major financial burden. The standard lease now costs about USD1 million each year, with strict conditions.

Perhaps most importantly, all progeny of the famously slow-to-breed pandas are Chinese citizens, and must return home on their fourth birthdays.

Rising tensions

However, tensions mean that the lease agreements with many western states are coming to an end without renewal. Of course, their ending is not a direct product of the worsening ties.

After all, panda negotiations are between China’s main wildlife organization and the relevant zoo, and so do not fall to relevant foreign ministries. Their lapsing is a product of bureaucratic inertia and lack of will.

Even so, the flight of pandas does act as a proxy, of sorts. The number of pandas in the US peaked at 15, for instance, but is now at a low. By the end of 2024, only one panda will be in the Americas – Xin Xin in Mexico City.

So with close American allies. The two pandas at Edinburgh Zoo will return home in December 2023, and those at Adelaide Zoo in Australia will return in a year or so. Other less confrontational states, such as Malaysia, continue to host pandas.

A Cold War indicator

All told, the departure of the pandas bears uncanny comparison with the panda drought from 1949 to 1972, and thus seems to confirm what we already knew – that a new Cold War is under way.

This fact stands, regardless of how well the meeting between Biden and Xi goes.

Leave a comment