Over the centuries, historians have sought to tell particular versions of Chinese history, based on certain preconceptions.

One contention is geographical, for instance, emerging from the features of the central plans (中原) in China – a triangle running from Xian to Shandong and up to Hebei province, roughly. This area is flat and dusty, but well-watered by the Yellow River (黄河), which is laden with silt from the loess plateaux inland, and hence is prone to flooding.

As such, the Chinese tell stories of great leaders such as Yu the Great (大禹), who tamed the waters with dams, dykes and channels. Indeed, some commentators have identified state efforts to control the waters as why Chinese governance has evolved as it did – with arguably greater emphasis on state control and organization of life and labour, than perhaps in Europe.

There is something to this claim, as Philip Ball has made clear in his book The Water Kingdom.

A Han dynasty image of Yu the Great (Wikipedia)

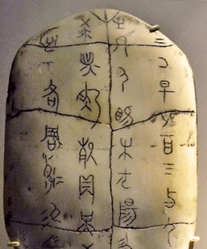

A second contention is more cultural, based around the use of written language. The first Chinese characters emerged in the jiaguwen (甲骨文), comprising carvings on animal bones cast into the fire for divination. That script has evolved over time, but certain continuities remain, and the Chinese system of writing lies still at the heart of Chinese culture.

Jiaguwen (Wikipedia)

Both of these approaches are accurate, and merit further exploration. However, this article will examine a third approach.

The drive to the South

The third approach has been the slow expansion to the south from the central plains, taking place mostly as settlement by farmers and those seeking to escape state control. People moved to frontier areas in the warmer south, where water was plentiful (unlike the north), but where the wilderness loomed large.

The changes took a long time, and the pattern of settlement was patchy, but in some ways recalled the settlement of Canada or the western United States. The expansion to the south also mirrors a shift to the north in Europe, which took place from the 10th century onwards, resulting in wealth and power moving from Mediterranean societies, such as Sicily, to those in northern Europe, such as the Netherlands.

Identifying when this shift took place is not easy. However, most activity in Chinese history from the Shang dynasty (roughly 1600 BC to 1045 BC), through the Warring States, Spring and Autumn and early imperial periods, took place in the central plains.

The south really meant the Yangzte River basin at this time; Sun Quan (孫權), who ruled the state of Wu in the Three Kingdoms period from 222 to 252, for instance, is often shown on maps as ruling to Guangxi and Guangdong.

In reality, though, the south of the kingdom ruled by Sun Quan was mostly a watery, mountainous wilderness, full of tigers and elephants. Some settlement had taken place down the coast, in the mouths of rivers, and in some valleys, such as around Guangzhou, but the inland was sparsely populated.

A key shift took place in the mid-Tang dynasty, however, prompted by the An Lushan rebellion (安史之乱). An Lushan was a monstrously fat but canny Turkic military governor or jiedushi (節度使) in control of northeastern China, who turned against the emperor in 755, marched on the capital Chang’an, and brought chaos on the dynasty.

The rebellion resulted in widespread death and destruction, and a breakdown in the Tang system of governance – as well as producing one of the great stories in Chinese history, about the emperor Tang Xuanzong’s (唐玄宗) tragic romance with his concubine Yang Guifei (楊貴妃), one of China’s “great beauties”.

Yang Guifei mounting a horse (c 1250)

In response, people fled south in droves, away from the battlefields, and carved out farms and settlements in remote areas. At this point, the south became more populous and prosperous than the north for the first time in Chinese history – a trend that has continued ever since.

This tilt to the south continued through the Song dynasty, especially after the loss of the north to the Jin and Liao in the 12th century, and during the Yuan and Ming dynasties, when the government took active measures to conquer Yunnan province and extend its sway into the mountains towards Burma and Thailand.

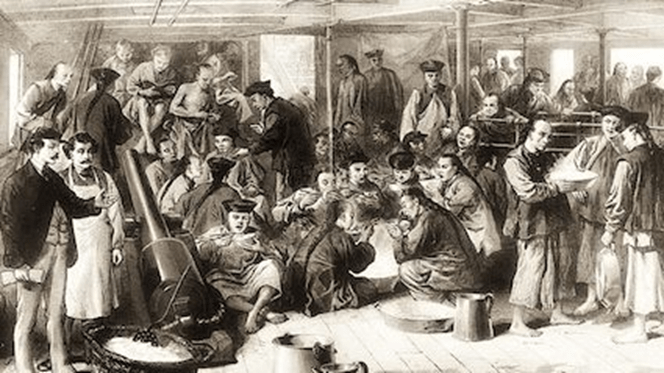

Similarly, the age of sail resulted in the movement of people further south, to southeast Asia (and to the US and Australia). Many were from Fujian or Guangdong provinces, driven by a lack of land and opportunity at home, and by the lure of wealth in trade or piracy. Chinese communities settled across Asia in the seventeenth century, often arriving alongside European colonisers, such as the Spanish in Manila or the Dutch in Batavia.

In many cases, the Chinese became the dominant commercial elite in such cities, benefitting from a lingua franca and a commercial and information network. Large communities of Cantonese speakers emerged in Malaya in the nineteenth century, working in the tin mines, for instance, while Fujianese traders dominated in Singapore and what is now Indonesia.

Chinese migrants to Southeast Asia in the nineteenth century

Government tended to follow settlement on the mainland, as various Chinese dynasties sought to tax and control those on the frontiers. Overseas was more challenging, of course, but the Qing dynasty even claimed jurisdiction over the overseas Chinese in Southeast Asia during the nineteenth century.

During the Cold War, some commentators even came to see the overseas Chinese as an extension of the government in Beijing – a “fifth column”. Hence, civil war emerged in British Malaya with the Malayan Communist Party (“MCP), a primarily Chinese party, in the 1950s, and appalling massacres of Chinese deemed pro-communist took place in Indonesia in 1965.

This perception was mostly exaggerated – many Chinese who moved overseas were seeking to escape the government – but was still powerful, fueled not only by anti-communist paranoia, but also by racism and envy of commercial success.

Few books tackle this subject – but it is one of the key trends in Chinese history, as important as the taming of the waters, or the development of writing. The best I have found is that by CP Fitzgerald, The Southern Expansion of the Chinese People.

His book was published in 1972, and is steeped in a sense that the Chinese diaspora was instrumental in the expansion of Communism across Southeast Asia in the 1960s and 1970s. Even so, it is excellent as history.

A major trend

The drive to the South continues to be a major driving force in Chinese policy today.

Take the dispute in the South China Sea. Beijing’s efforts to assert control over the sea recall prior efforts to extend control to the frontier.

In the case of this dispute, China’s legal claims (the notorious Nine Dash Line), emerged from Kuomintang government assertions in the 1940s, and hence have continuity over at least two “dynasties”.

Now, this issue is coming to head, driven by Beijing’s efforts over the last decade to seize reefs in the South China Sea, and to build bases from which to project force.

The Nine Dash Line (Wikipedia)

Tensions over the South China Sea could easily result in conflict between China and a range of disputants, such as the Philippines and Vietnam, and perhaps even the US.

Indeed, in September and October 2023 concerns arose about efforts by the Chinese Coast Guard to prevent the Philippines authorities from restocking the BRP Sierra Madre, a rusty former American World War Two vessel stranded on a tropical reef.

Those dealing with this issue need to understand, though, that China’s desire to exert control over the South China Sea is not just a “flash in the pan”. Rather, Chinese policy sits within the context of a centuries-long drive to the south.

Leave a comment